Urethral Stricture After Prostate Surgery Or Radiation

Home > Prostate Cancer Complications > Urethral Stricture After Prostate Surgery Or Radiation

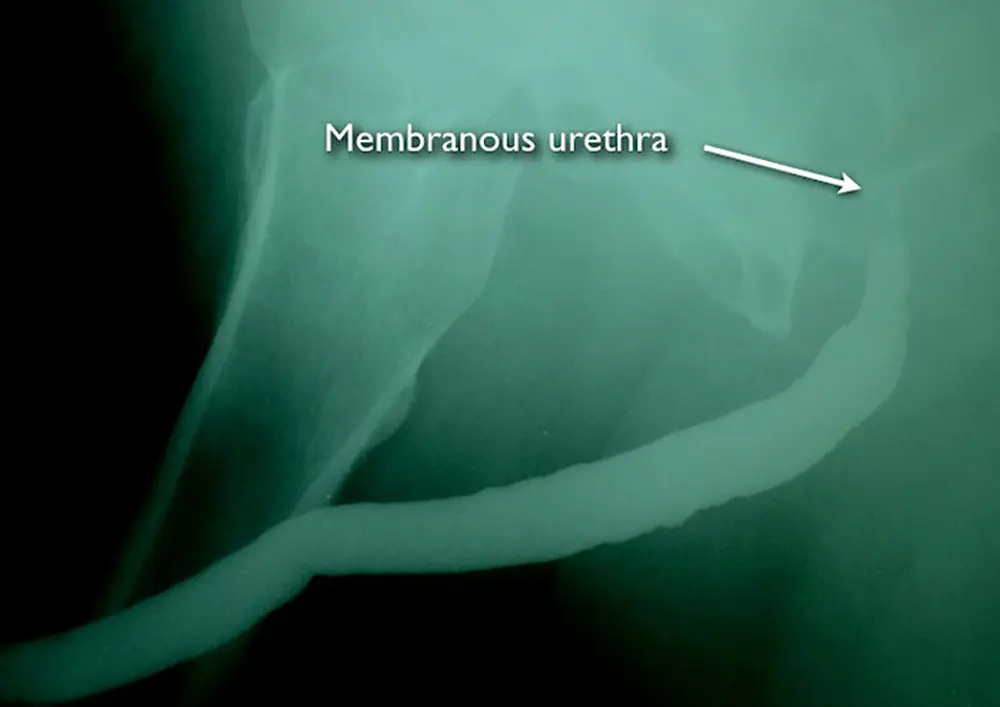

This is the retrograde urethrogram (RUG) of a patient with a membranous stricture. This study confirms a normal anterior urethra. This study does not diagnose narrowing of the membranous urethra because this portion of the urethra is normally closed when a patient is not urinating, and during a RUG, the patient is not urinating.

With the gentle injection of X-ray contrast to fill the bladder (a catheter should never be used for this purpose), we can then obtain a film during urination called a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG)

During urination with a bladder filled with X-ray contrast, the voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) shows that the bladder neck opens normally. However, there is severe narrowing of the membranous urethra.

The voiding cystourethrogram confirms that the bladder neck and the urethra within the prostate itself are without any narrowing. When the information from the cystoscopy and imaging is taken together, it can be determined that there is urethral stricture narrowing of only the membranous urethra just under the prostate.

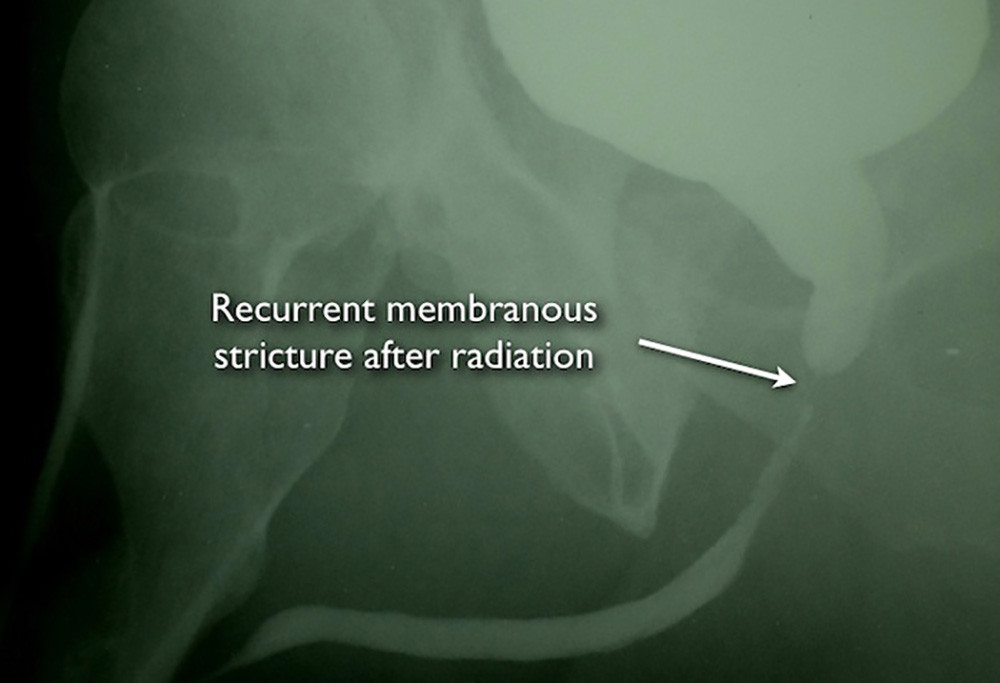

Treatment options include dilations and internal incisions. However, these are quick fix procedures generally only associated with temporary improvement of symptoms, and repeated dilations and incisions of stricture can make the stricture worse.

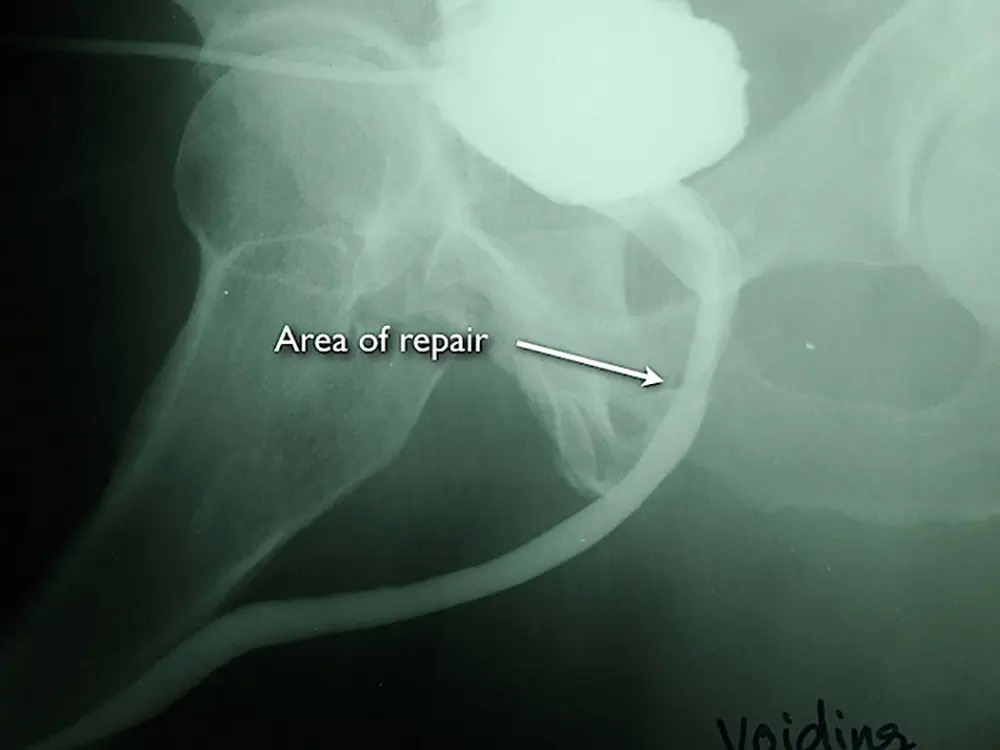

Fortunately, these strictures are highly amenable to posterior anastomotic urethroplasty, an operation that involves an incision under the scrotum under general anesthesia, the removal of the involved tissue, and a re-connection of the wide-open ends. Men with urethral strictures in the membranous urethra surrounded by the external sphincter are very concerned about developing urinary incontinence as a side effect of open urethroplasty surgery to treat the stricture. However, if the bladder neck is functioning normally, urine will stay in the bladder except during urination.

This is the VCUG after open repair, urethroplasty, with excision of the narrow area and reanastomosis. His surgery was 18 years ago, and his urethra remains patent without the need for dilations or other treatment.

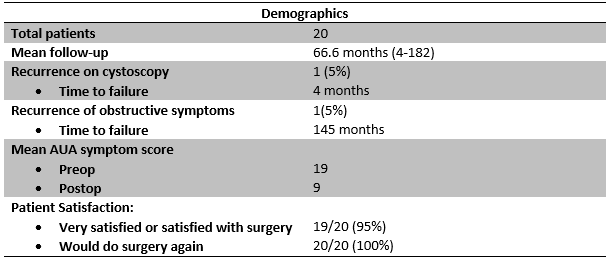

The success rate of these surgeries is highly dependent on the skill and expertise of the Urologist performing this operation. We have seen patients whose Urologists attempt these surgeries and seem to have a 100% recurrence rate. This year, we reviewed our long-term outcomes with posterior urethroplasty for radiation urethral strictures involving the membranous urethra in patients who were compliant with long term follow-up (see table 1).

After surgery, our protocol is to look at the inside of the urethra with a cystoscope 4 months after surgery. This is done in our clinic without the need for sedation. We use a high-definition monitor to assess the urethra. Early success is defined as a urethra open enough that the size 16 French scope (16mm circumference) can pass through the area the repair easily. Only 1 patient had narrowing of the urethra at the connection to where the scope could not pass. However, the urethra was only very slightly smaller, the patient had no symptoms, and he did not require further treatment. In all other patients, the urethra was wide open.

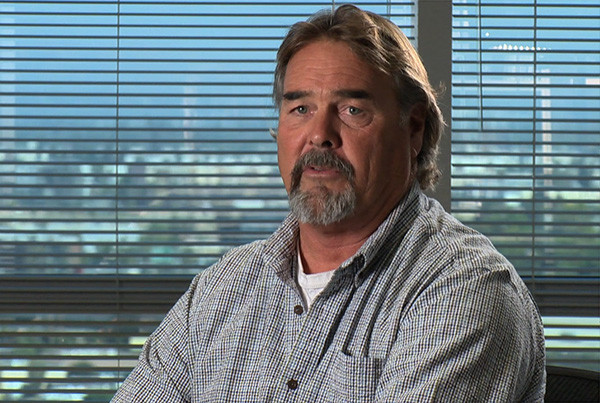

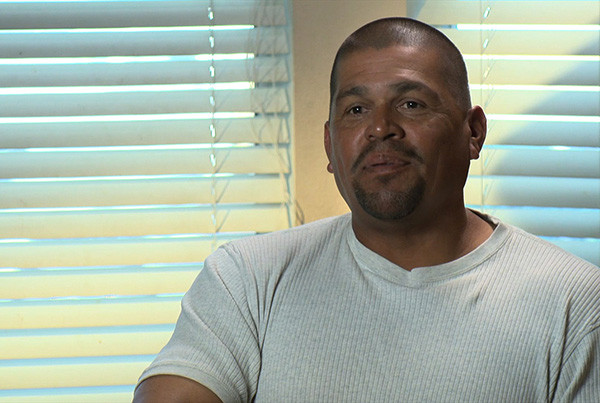

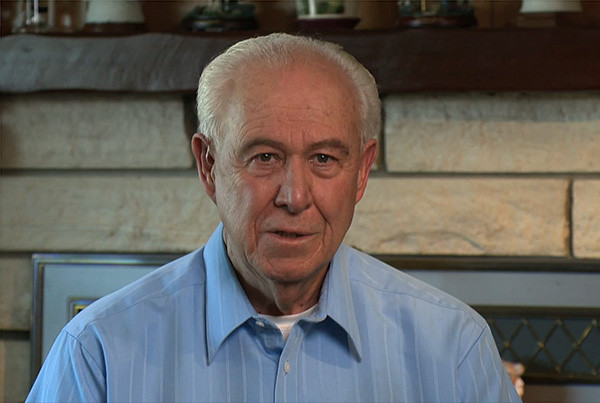

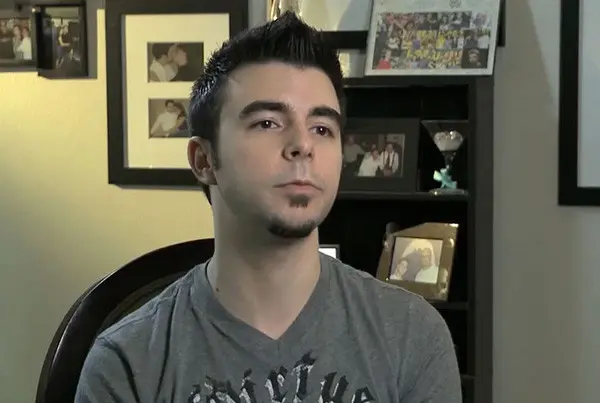

We also monitor our patients for late recurrence with long-term followup given that we have 18 years of experience performing this and other urethroplasty surgeries (over 2,000 total cases). Only 1 patient developed some narrowing 145 months (12 years after surgery). One patient did develop some unanticipated incontinence and was not completely satisfied with the result. However, that patient and all other patients were asked “If you could do things over again, knowing what you know now about the result, would you still have the surgery?”. All of the patients (100%) said “yes”.

Our results should not be interpreted as a guarantee of success, but clearly prove that posterior urethroplasty, performed at the Center for Reconstructive Urology, generally offer our patients a cure and a markedly improved quality of life.