Dilation, Urethrotomy, Stent

Home > Urethral Stricture > Dilation, Urethrotomy, Stent

After a urethral stricture diagnostic evaluation, a urologist will decide which treatment method is best to widen the narrowed portion of the patient’s urethra. There are various different types of treatments, all of which are appropriate in different circumstances and situations. Depending on the symptoms exhibited and the results of the diagnostic evaluation, a patient may be treated with a urethral stricture dilation, or an internal urethrotomy (DVIU). In the past, Urethral stents (called the Urolume®, made by AMS – American Medical Systems) were a treatment option, but these were found to be a poor option and taken off the market.

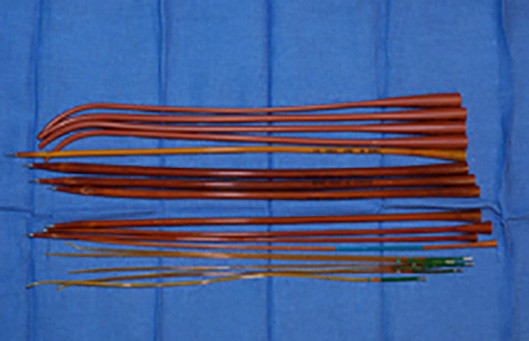

Van Buren Sounds

Filliforms and Followers

The filiform is a long and very narrow instrument that is advanced through the urethral stricture to aid in the dilation process. Once the filiform is advanced easily through the stricture, it is attached to progressively larger dilating instruments. These dilating instruments are then carefully guided through the stricture, providing progressive dilation.

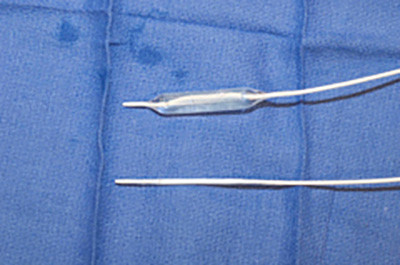

Another stricture dilation method is called balloon dilation. This technique involves a specialist gently advancing a flexible tip guidewire through the stricture. Once the guidewire has reached the stricture, a balloon dilating catheter is advanced over the guidewire, and the balloon is guided to the area of narrowing. In the past the balloon had to be guided as a blind procedure, meaning that the specialist had no visibility of the inside of the urethra as they attempted to treat the stricture. However, in 1998 Dr. Gelman developed a balloon dilating catheter, now commercially available (Cook Urological and Boston Scientific – called the Uromax), that allows the stricture to be dilated under direct vision. This incredible innovation has made balloon dilation easier and safer than other dilation methods, leading to the device being published on the cover of the Journal of Endourology in 2011. Performing the procedure under direct vision may be associated with a lower complication rate, as blind dilation methods can result in complications such as false passage and urethral perforation.

Unopened as Seen Through a Scope

Balloon Dilator Closeup

Opened as Seen Through a Scope

Balloon Dilator Package

Dr. Gelman has no commercial interest in this or other devices and has never accepted royalties to avoid any conflict of interest.

Once the balloon reaches the area of narrowing, it is slowly inflated. Then the balloon is subsequently deflated, and the dilating catheter and guidewire will be removed. Alternatively, some specialists will keep the guidewire in place and insert a temporary stenting catheter over the guidewire after the balloon is deflated.

After initial dilation, the patient may have a temporary and/or intermittent urethral catheter placed to prevent the urethra from immediately narrowing again. In some cases, following urethral dilation, a patient may be asked to perform self-catheterization. Self-catheterization is a procedure where the patient will periodically insert a catheter (tube) into his urethra in an attempt to prevent stricture recurrence, using the catheter as a dilating instrument.

The DVIU procedure begins with the endoscopic instrument inserted into the penis. Near the tip of the instrument is a small blade that can be deployed once the stricture is reached, cutting the stricture internally to “open it up” in one or more places. Once the stricture is opened, an indwelling catheter is placed to keep the urethra open while the urethra heals, which usually takes somewhere between 3 and 5 days.

Some patients are under the false impression that this procedure “cleans out” and removes scar tissue. However, the urethra does not have a build-up of scar tissue inside that can be scraped out. Instead, with urethral stricture disease, the urethra itself is narrow.

After the catheter is placed, the best outcome would be for cells to grow into the open wound so that when the catheter is removed, the urethra remains at a healthy width. This is called epithelialization. Unfortunately, what usually happens is something called wound contraction. Wound contraction is when the body responds to the incision by forming a contracted scar, which can lead to recurrent strictures. The reality is that patients treated with multiple incisions can oftentimes find the procedure complicated by recurrence.

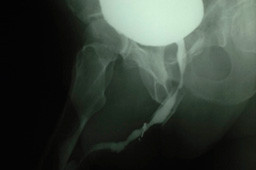

The urethral stent was placed into the urethra endoscopically (through the penis) after the stricture was incised. The objective was for the stent to stop the urethra from contracting as scarring again occurs, preventing the recurrence of strictures. As the lining of the urethra heals, the concept was that it would eventually cover the stent, keeping the stent in place permanently. While this procedure was technically simple to perform, it was unfortunately associated with a high failure and complication rate, as strictures often formed despite the presence of the urethral stent.

Although the urethral stent was once thought to be an excellent treatment option for recurrent bulbar urethral strictures, it has been shown to compare very unfavorably to open repair. When patients developed strictures after a urethral stent has been placed, the repair was considerably more challenging than it would have been otherwise. These complications resulted in the Urolome urethral stent being taken off of the market, and it is no longer available.

At UC Irvine, we have successfully reconstructed the urethra of many patients referred to our institution after stent failures, and our results were published in the Journal of Urology in 2007. All of our patients have had a technically successful outcome following open repair, making it the best option for patients with recurrent urethral strictures after urethral stent placement.

Before

After