Pelvic Fracture Urethral Injury

Home > Urethral Stricture > Pelvic Fracture Urethral Injury

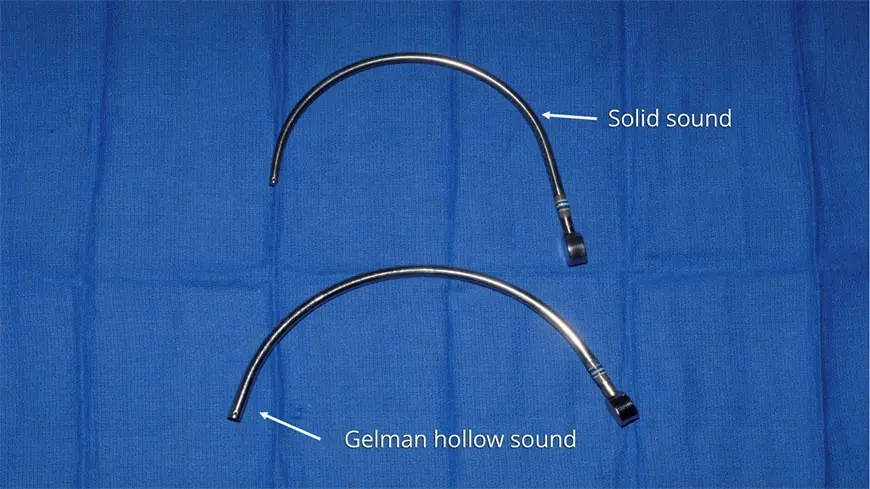

Fortunately, these injuries can be effectively repaired. The Center for Reconstructive Urology has a 21-year history of successfully repairing torn urethras with a 99+% technical success rate. Our incredibly high success rate even includes more complex cases in which patients have had one or more failed surgeries by other Reconstructive or General Urologists, and then came to us for a successful re-do surgery. Detailed information about our approach and the development of specialized, cutting edge instrumentation by Dr. Gelman to facilitate a successful repair, can be found in his most recently published surgical textbook chapters on the subject:

Posterior Urethral Strictures article in Advances in Urology volume 2015

This section of our educational website is for men who suffered a pelvic fracture urethral injury or tear. It details the best way to have a pelvic fracture urethral injury effectively evaluated and permanently fixed so they can go back to living a happy and healthy life. It is essential to learn as much information as possible to make for informed consent to any and all treatment. An inexperienced surgeon may attempt treatment and fail, and it is important to know what options remain after ineffective treatment. We are seeing more and more men with one or more failed repairs who are mistakenly told that their only option is to repeatedly insert catheters into their urethras to keep the area of injury open. This is simply not the case, as there are various other treatment options.

Initial Evaluation and Management of Pelvic Fracture Urethral Injury

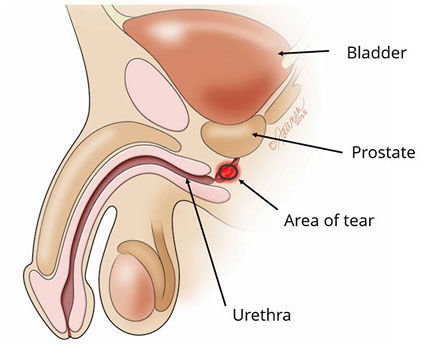

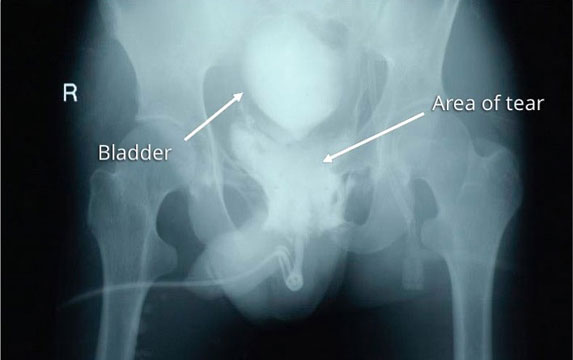

Patients who suffer pelvic bone fractures from trauma are immediately transported by ambulance to the nearest Emergency Room. In general, many of these patients are found to have blood at the tip of the urethra, which is a sure sign of a pelvic fracture urethral injury. If this is the case, the next step is to confirm the diagnosis, and an appropriate diagnostic evaluation is performed using a urethral imaging X-ray study retrograde urethrogram (RUG).

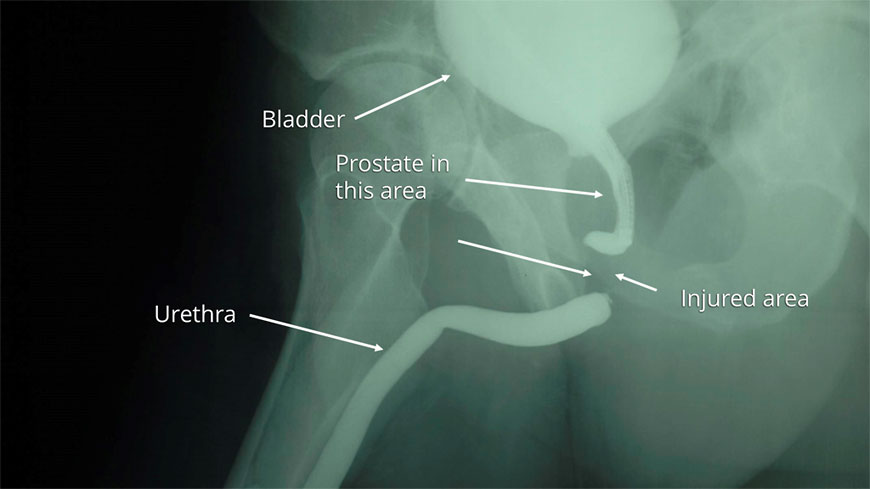

This image is a retrograde urethrogram (RUG) obtained after pelvic trauma caused a urethral injury. A contrast fluid was injected through the urethra, and in the image, the contrast did not remain contained within the urethra. Instead, it escapes through the area of the tear into the surrounding tissues, confirming the diagnosis. This is called contrast extravasation.

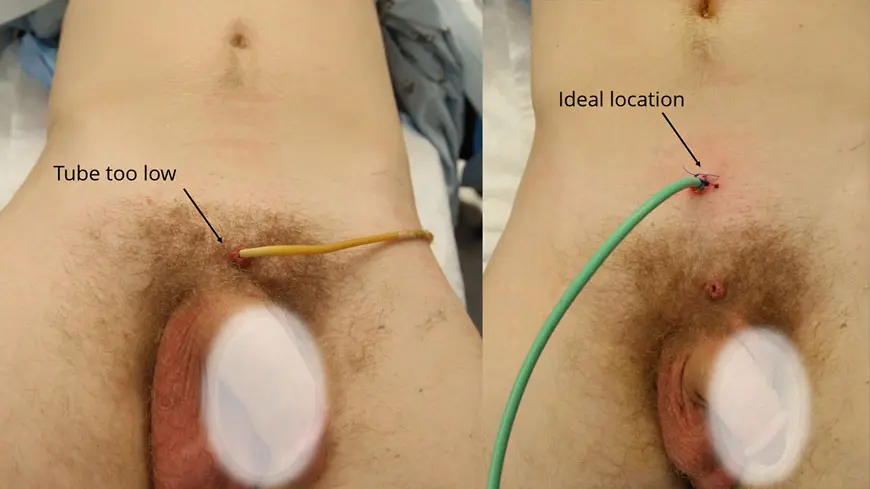

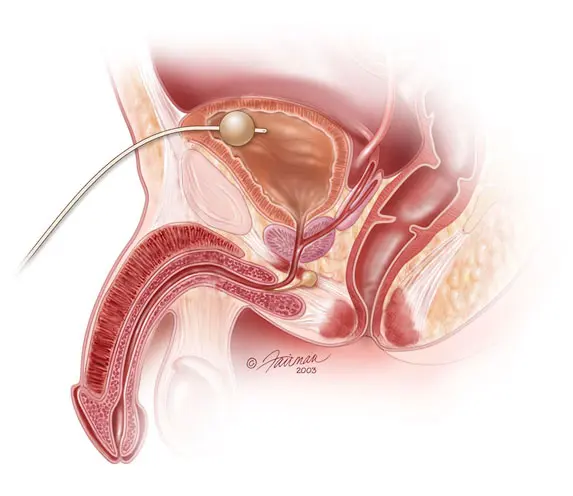

Men who suffer a complete tear of the urethra are unable to urinate, requiring the placement of an emergency suprapubic tubes immediately after the injury. A suprapubic tube is a catheter that enters the bladder directly through the area between the penis and belly button, commonly known as the lower midline abdomen. This allows for urine in the bladder to pass through the tube and then drain into a collection bag, letting the bladder successfully empty of all fluids. Since this bladder drainage tube is what allows the bladder to empty as the urethra is stabilizing, it is important that this tube be of proper size and location.

The suprapubic tube is placed through a small hole in the skin between the penis and umbilicus (belly button) to allow for direct access to the bladder. A small balloon is inflated at the tip of the catheter inside the bladder to keep the catheter from sliding out.

If the urethra is completely torn, a Urologists may choose to perform a surgery called Primary Realignment. The objective of this surgical procedure is to push a catheter through the penis and the area of injury, leading it into the bladder. The idea behind a Primary Realignment is that as healing occurs and the blood surrounding the injury (hematoma) gets reabsorbed back into the body, the presence of a stenting catheter will allow the severed ends of the urethra to come together. Therefore, when the catheter is removed, the hope is that the urethra will remain open. If not, this “realignment” will lead to subsequent surgery.

The relative effectiveness of a Primary Realignment is the subject of some controversy among Urologists. At the Center for Reconstructive Urology, we do not consider this technique to be effective when treating a complete urethral tear that developed as a result of a pelvic fracture. What is not controversial is that if a urologist completes a Primary Realignment and the catheter eventually comes out, under no circumstances should the urethra be repeatedly catheterized to “keep it open” in an effort to avoid surgical repair. This will not be curative and will instead result in an unnecessary delay of actual curative treatment.

Delayed Repair of Pelvic Fracture Urethral Injury

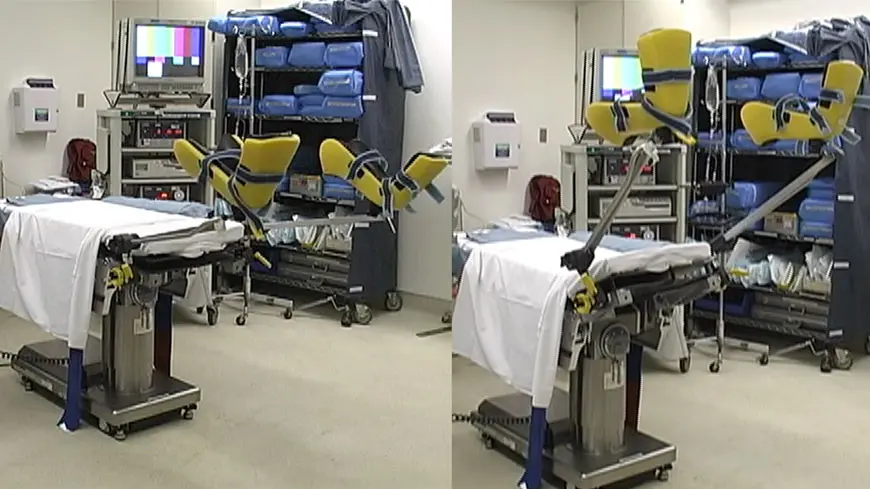

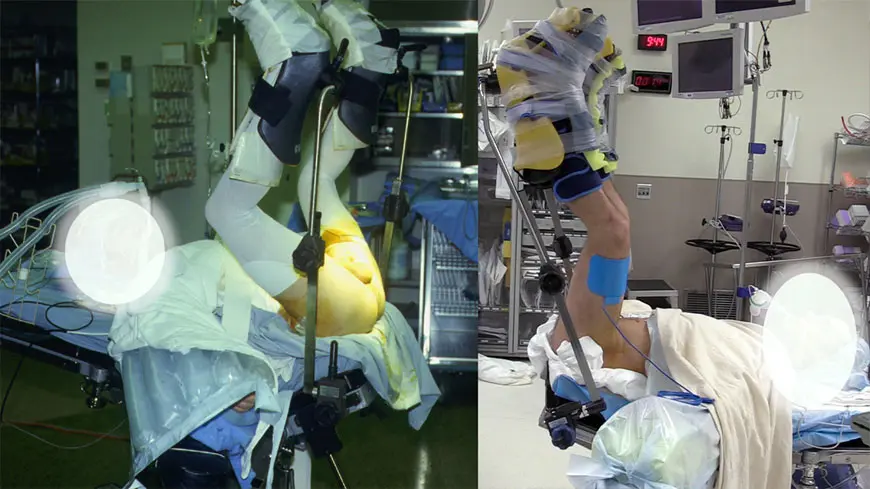

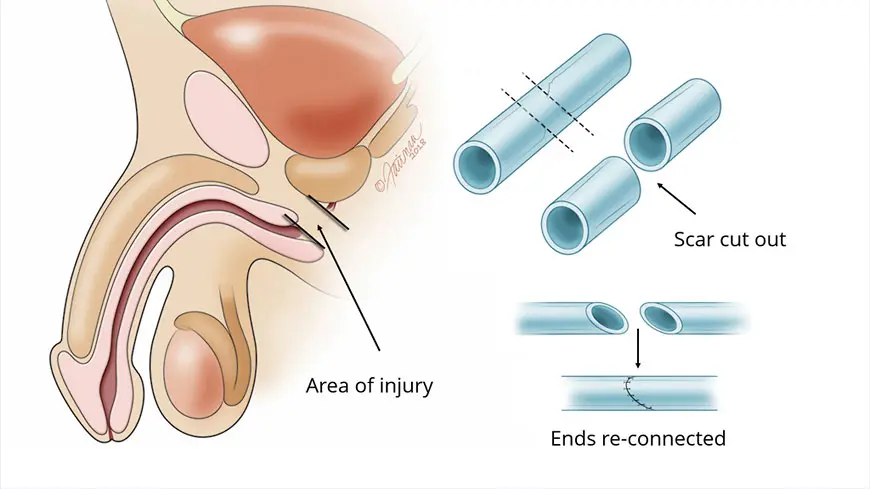

While most men with urethral tears and suprapubic tubes yearn for immediate surgical repair, they will usually have to wait for treatment. We advise that they wait approximately 3 months with the suprapubic tube before undergoing surgical repair, called posterior urethroplasty. If a patient is healing from other issues, such as other bone fractures, they will need to wait even longer. All other injuries need to first heal before we are able to do urethral surgery. During this crucial healing time, the torn severed urethra seals off and the swelling in the surrounding tissues goes down. As the patient waits for surgery, the suprapubic tube allows for the bladder to empty.

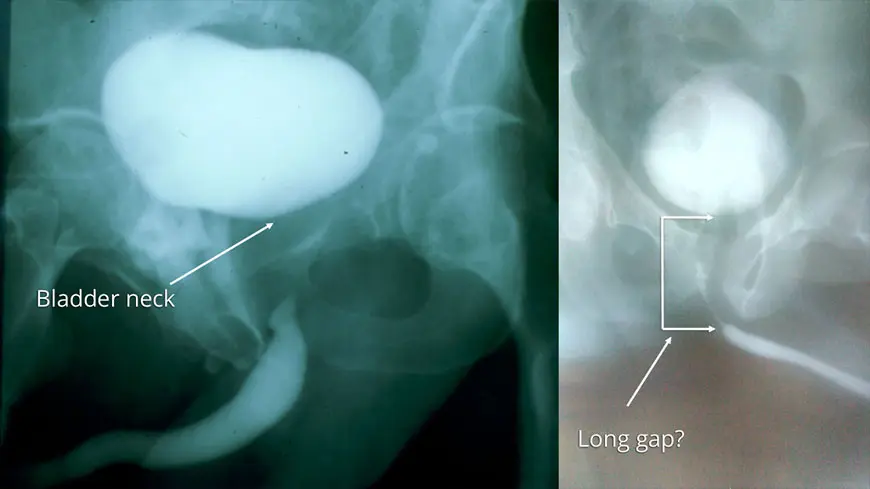

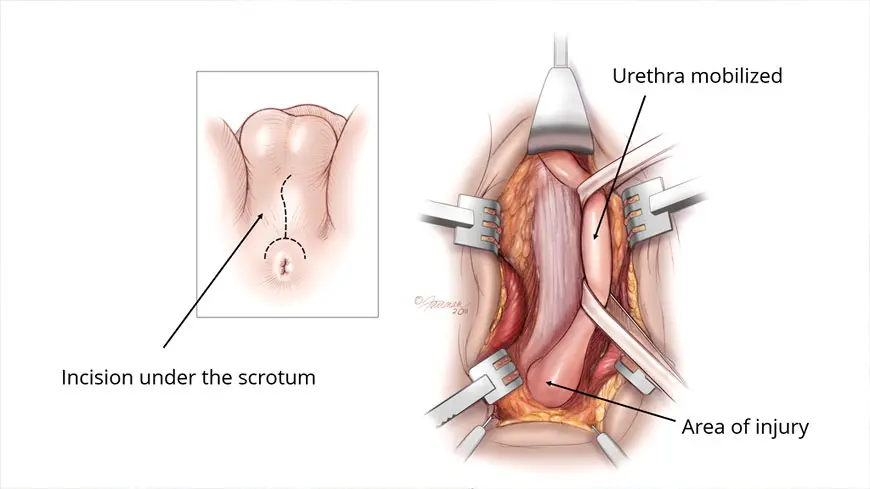

After around three months of healing occurs, the urethra will no longer be torn. However, there will be significant scarring in the area surrounding the urethral tear, and the 2 ends will not be successfully connected. The main purpose in delaying evaluation is so that the exact length and location of the defect can be precisely determined in preparation for surgery.

Evaluation of a Torn Urethra Prior to Surgery

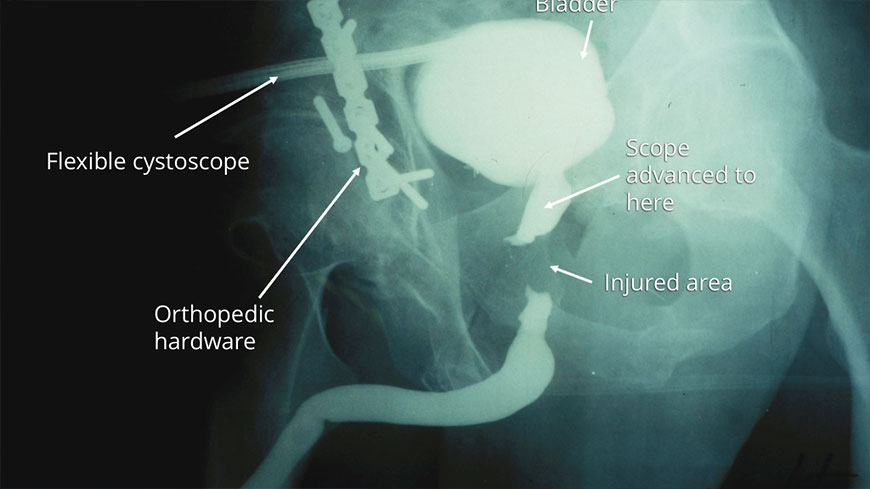

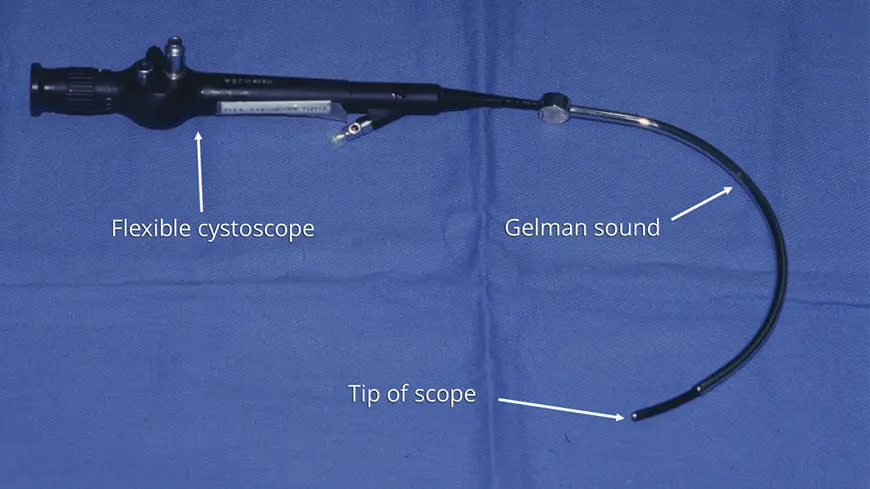

The evaluation process of patients with posterior urethral disruptions consists of simultaneously performing a retrograde urethrogram and a cystourethrogram. A retrograde urethrogram involves injecting contrast through the urethra from below and capturing images of what occurs, and a cystourethrogram involves inserting a scope through the tract established by the suprapubic tube from above. It is our preference to perform these tests in the operating room.

The following slide show provides pictures and information describing the various methods we use to evaluate patients before surgery.

Those patients who suffer traumatic urethral injuries often have associated vascular and nerve damage affecting the penis and urethra, and over half suffer erectile dysfunction as a result of the injury. We evaluate the vascular status prior to urethral reconstruction using an ultrasound test called a Penile Duplex. Most patients, even with some arterial compromise, have enough blood flow to have their urethras repaired without concern about proper healing. This test confirms adequate blood supply to the urethra. Occasionally, we document severe impairment, and in these cases, perform a revascularization procedure prior to urethral reconstruction so that the urethra will then have adequate blood supply at the time of repair. This is very rarely required.

In summary, when a man suffers a urethral tear, the initial management is placement of a bladder drainage tube called a suprapubic tube and patience is required as the tissues heal for at least 3 months. Then, before posterior urethoplasty surgery to repair the urethra, what is needed is:

Our patients are maintained with urethral catheters and suprapubic tubes for 3 weeks after surgery, and then return for an imaging test called a voiding cystourethrogram. In general, at that time, both tubes are then removed, and our patients resume normal urination without need for further intervention.

The image on the left was taken of one of our patients prior to surgery to repair his pelvic fracture urethral injury by a posterior urethroplasty. The image on the right was the post-operative imaging called a voiding cystourethrogram. This image after surgery was obtained by easily filling the bladder with contrast and then taking a film during urination. The image shows a wide open urethra and a “water tight” repair.